Spirit Horses of Yakutia

Guardians of Ice and Ancestry

In the vast, frozen expanse of Yakutia, where the cold can cleave breath from the lungs and the ground lies locked beneath ice for most of the year, a small, shaggy horse survives against every odd. The Yakutian horse, locally known as Sakha ata, does not merely endure the cold — it thrives in it.

With frost-crusted whiskers and thick winter coats, these horses form living shadows across the snowfields, enduring temperatures as low as -60°C without shelter or human aid. Here in the Sakha Republic of Russia's Far East, the bond between horse and human is not ornamental or recreational. It is ancestral, spiritual, and essential.

The Sakha people, Indigenous to this remote and formidable region, do not see horses as animals to be dominated. Rather, they are seen as beings of immense spiritual power.

In Yakut cosmology, horses are messengers between the earthly and spirit worlds, carrying the souls of the dead to the afterlife. They are also believed to possess their own spirits, requiring respect and ritual.

A herder may whisper a blessing or burn juniper before a journey. A foal’s birth is greeted with joy and offerings, not merely as new stock, but as a spiritual addition to the herd.

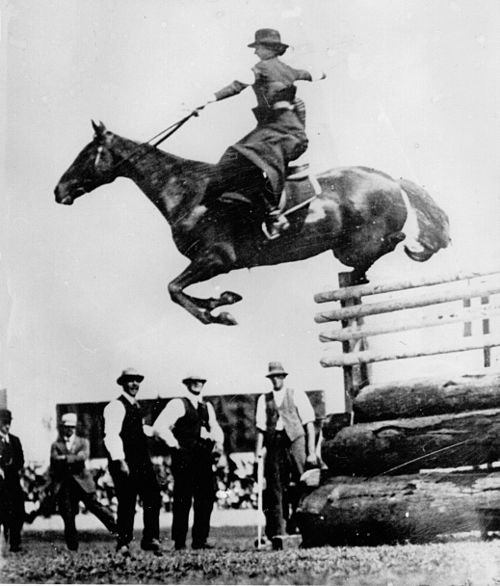

Horses looking for grass beneath the snow

The Yakutian horse itself is a marvel of evolutionary resilience. Descended from ancient equines that adapted over millennia to Arctic conditions, the breed developed a physiology uniquely suited to this harsh terrain. Compact and powerful, with small ears and a low metabolic rate,

Yakutian horses can locate lichen and frozen grasses beneath thick snow. Their winter coat, sometimes growing over 15 centimeters long, insulates them through the darkest, coldest months, while a layer of body fat provides critical warmth and energy.

Unlike many domestic breeds, Yakutian horses are largely left to roam semi-wild across the taiga and tundra, herded only during seasonal round-ups or when needed for work. They form complex social bands and learn to navigate deep snow, icy rivers, and predator threats with minimal human intervention. In this way, they mirror the independent, resourceful spirit of the Sakha themselves.

Horse being milked

Despite their modest size, these horses play a central role in everyday survival. They pull sleds through snow-locked terrain, provide a source of milk for kumis (a fermented drink believed to have medicinal properties), and supply meat during the long winters.

These uses are not taken lightly; the act of butchering a horse involves ritual acknowledgment of the animal’s sacrifice. Nothing is wasted. Every part of the horse — from hide to bone — finds purpose.

Traditions persist, but the world is changing. Climate instability alters the snowpack and pasture cycles, threatening the delicate balance that sustains free-ranging herds. Younger generations increasingly seek opportunities in Yakutsk or beyond, where modernity eclipses the rhythms of horse culture.

And yet, there is revival too. Local breeders, researchers, and elders collaborate to preserve the Yakutian horse’s genetic purity. Some advocate for national recognition and international heritage status. Others welcome curious travellers willing to brave the cold and learn.

In a land where breath can freeze in midair and the sun disappears for months, survival is more than a matter of strength — it is a matter of relationship. Between man and land. Between breath and belief. Between rider and horse.

To follow the tracks of a Yakutian horse across the tundra is to step into a world where endurance is sacred, and the past still walks beside the living

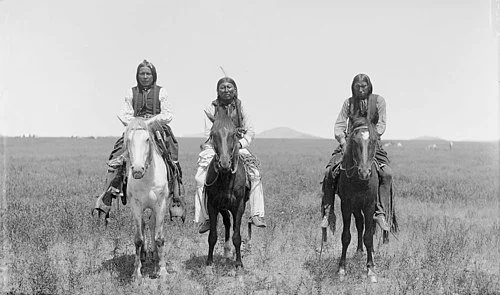

Rider in traditional clothing and tack