Women, Horses, and Tradition in Mexico’s Arena

An all-female equestrian team discipline where precision riding, cultural heritage, and collective responsibility come together in the arena.

Before the music starts, before the horses enter the arena, Escaramuza already exists in quieter moments — a woman tightening a cinch, smoothing a skirt, braiding a child’s hair beside the trailer. What follows in the arena is exacting and disciplined, but it is shaped long before competition day. This is not preparation for a performance. It is preparation for continuity.

Origins and Formalisation

The word Escaramuza translates roughly to “skirmish” or “maneuver,” referring to fast, coordinated movement rather than combat itself — a definition that aligns with the discipline’s emphasis on speed, precision, and formation.

Escaramuza developed as the female counterpart to Charrería, Mexico’s national equestrian discipline.

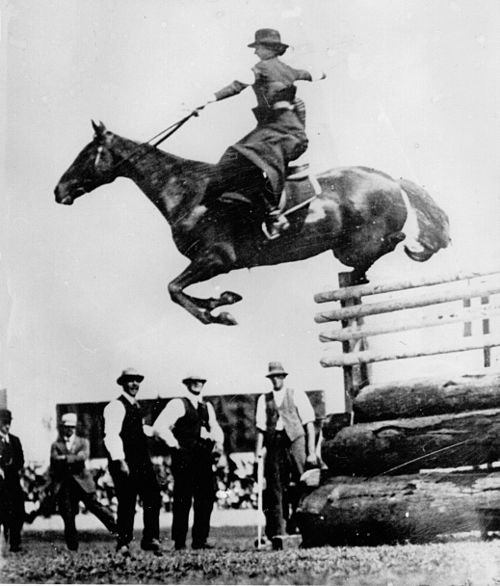

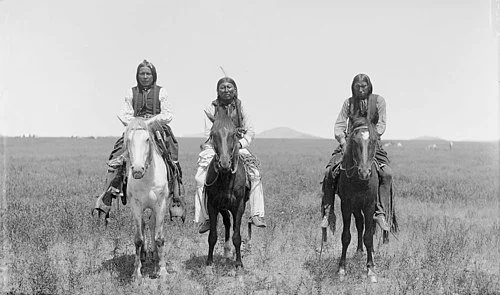

Its imagery and dress reference the Soldaderas — women who supported and fought alongside revolutionary forces during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). These women rode horses for transport, logistics, and military movement, often riding sidesaddle due to clothing and social conventions of the period.

Escaramuza itself did not exist as a formal sport during the revolution. It emerged in the 1950s, as charrería became increasingly organised and rule-based.

Women’s riding exhibitions were formalised into an all-female team discipline, with eight riders performing choreographed routines at speed.

Standardised movements, scoring criteria, and uniform requirements transformed informal displays into a regulated competitive event.

During this period, the Adelita-style dress was codified as official attire, visually linking the modern discipline to revolutionary-era women.

Today, Escaramuza is practiced in Mexico and internationally as a structured, judged team discipline. While its presentation draws on historical reference, its modern form is the result of mid-20th-century institutional development rather than direct revolutionary practice

Female charras or "escaramuzas" in a charrería tournament. Mexico City, 2017.

Charras after the ride

Escaramuza — At a Glance

| Discipline | All-female equestrian team riding discipline from Mexico |

| Cultural Context | Part of charrería, Mexico’s national equestrian sport rooted in traditional ranch skills |

| Team Format | Eight riders performing together in a single coordinated routine |

| Riding Style | Ridden sidesaddle at canter and gallop |

| Key Movements | Circles, crossings, direction changes, tight formations |

| Judging | Precision, timing, formation, and collective control |

| Scoring | Team-based only — no individual scores |

More Than a Sport

Escaramuza is often described as elegant or folkloric, but those labels barely touch what it demands of the women who ride it. For them, Escaramuza is a discipline built on responsibility, precision, and collective commitment.

As one rider explains, “Escaramuza gives us independence. It gives us confidence. It gives us tools we can use within our community.” What happens in the arena reflects those values. Precision is non-negotiable. Teamwork is essential. Individual ability matters only insofar as it serves the group.

Escaramuza performing the Cala de Caballo.

Riding as a Collective Act

Escaramuza demands absolute synchronisation. Eight riders move as a single unit, often at speed and often within inches of one another. Circles tighten, lines cross, directions reverse. One mistake ripples through the entire formation.

Horses are selected and trained with care. They must be calm, steady, and mentally resilient — capable of working sidesaddle amid music, movement, crowds, and swirling skirts. Training is deliberate and patient, grounded in trust rather than force.

Cleanliness — limpieza — matters. Straight lines matter. Transitions matter. What looks graceful to the audience is, in practice, control under pressure.

Escaramuza charra in Oaxaca

The Adelita Dress: Heritage Worn, Not Displayed

The Escaramuza uniform is not costume. Inspired by the Adelitas of the Mexican Revolution, it consists of a long, full skirt, fitted bodice, high neckline, and regional embroidery, all governed by regulation and tradition.

Riding sidesaddle at speed in this dress is technically demanding. Managing fabric while maintaining balance, posture, and rein control requires strength and experience. The beauty audiences see is earned through mastery, not decoration

Female and male charro regalia, including sombreros de charro

Family, Friendship, and Generational Bond

Throughout Escaramuza, the same themes surface repeatedly: family, friendship, and inheritance. Teams often become extended families. Young girls grow up around the arena, watching mothers, sisters, and aunts ride before taking their own place in formation.

One rider speaks of identity — not as something abstract, but as something practiced. Maintaining these traditions gives us identity. Escaramuza is passed down not through instruction alone, but through example.

For Mexican communities abroad, particularly in the United States, Escaramuza has taken on an additional role: preserving cultural continuity far from home.

Why Escaramuza Endures

Escaramuza survives because it teaches more than riding. It teaches cooperation, patience, and accountability. It demands responsibility — to the horse, to the team, and to the tradition itself. Strength here is quiet and earned through repetition, reliability, and consistency, not display.

Riders often speak about wanting young girls to see what is possible — to see that grace and seriousness, beauty and control, can exist together. What the audience sees is colour and motion. What lies beneath is structure, heritage, and commitment, renewed every time eight riders enter the arena together.

Escaramuza is inseparable from the history of women riding sidesaddle. To explore how side saddle developed, why it was used, and how it shaped women’s riding traditions across cultures, read our companion piece:

The History and Evolution of the Side Saddle →