The Side Saddle

An Evolution Shaped by Constraint, Craft, and Culture

Conception and Early Form

The side saddle was not created to improve riding performance. It was created to satisfy a social rule.

In medieval and early modern Europe, upper-class women riding in public were not permitted to ride astride. Astride posture was associated with labour, warfare, and masculine authority. For women of rank, appearance on horseback carried social meaning: posture, dress, and restraint mattered as much as movement. The side saddle emerged as a mechanical solution to this restriction, allowing women to appear mounted without violating expectations of propriety.

Its earliest forms reflected this clearly. Medieval side saddles were not riding saddles in any technical sense, but pillion or chair-type seats, often mounted behind a male rider and facing sideways. Balance and control were minimal. The rider functioned as a passenger rather than an independent horsewoman, and the saddle’s purpose was transport and display rather than horsemanship.

As women increasingly rode alone, design shifted incrementally. By the late medieval period the rider was turned forward and a single fixed pommel introduced, allowing the right leg to hook over the saddle. This improved orientation and basic stability, making rein control possible. Even so, lateral security remained limited, and riding was confined to controlled paces and forgiving ground..

Woman riding in a modern English sidesaddle class

Technical Maturity and Peak Development

The decisive transformation came in the late eighteenth century with the addition of the second pommel — the leaping head — positioned beneath the rider’s left thigh. This single innovation converted the side saddle into a stable riding system. With the pelvis supported between two fixed points, balance became structural rather than tentative. Riders could now travel at speed, negotiate uneven ground, and jump obstacles by absorbing movement through the core rather than gripping for security.

With the leaping head, the side saddle ceased to be a compromise and became a system.

Nowhere was this system pushed further than in Britain. Nineteenth-century fox hunting demanded endurance, speed, and jumping over solid country. British saddle makers refined pommel geometry, seat balance, and girthing to manage asymmetrical load and prevent roll. Skilled riders hunted side saddle under conditions as demanding as those faced by astride riders. This period represents the technical peak of side saddle development — driven by necessity rather than ornament.

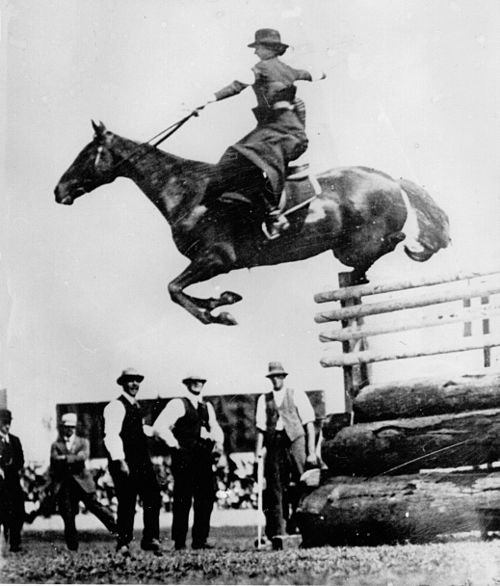

Mrs. Esther Stace riding sidesaddle and clearing 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in)

Queen Elizabeth II riding side-saddle

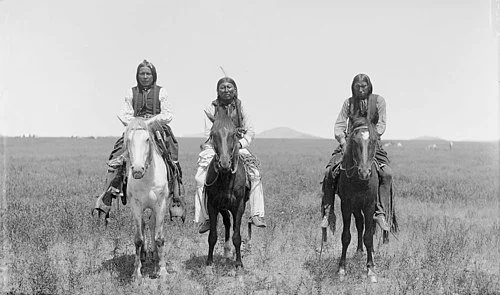

Divergence: America and the Colonies

When the side saddle crossed to North America, its evolution diverged. American riding culture developed under different pressures. Astride riding was accepted earlier, particularly beyond the eastern elite, while frontier and stock work prioritised practicality over display. As a result, the American side saddle became a lighter, flatter offshoot of the European line.

American examples typically show less aggressive leaping heads, flatter seats, and reduced emphasis on maximum lateral lock. These saddles were well suited to park riding, social use, and light hunting, but were rarely pushed to the extremes seen in British cross-country work. This was not a failure of design, but a response to circumstance. Once astride riding became socially acceptable, there was little incentive to continue refining the side saddle toward peak performance.

In colonial regions such as India, Australia, and parts of Africa, the side saddle was adapted rather than reinvented. European structures were retained, but materials, padding, and girthing were modified for heat, distance, and mixed terrain. These adaptations emphasised endurance and practicality while still conforming to social expectations where they persisted..

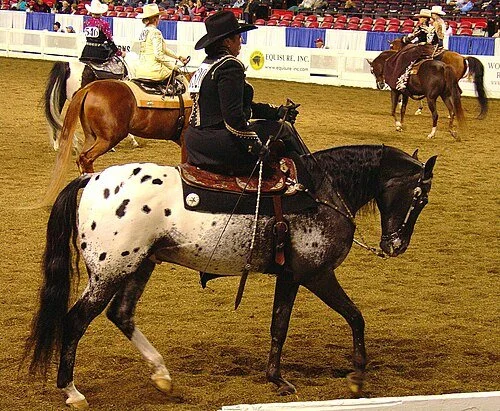

Western sidesaddle class

Refurbished antique "catalogue" saddle, manufactured circa 1900.

Decline and Survival

By the early twentieth century, the forces that had created the side saddle had largely dissolved. Women rode astride openly, equestrian sport standardised, and practicality overtook convention. The side saddle declined not because it was unsafe or ineffective, but because the social restriction that necessitated it no longer existed.

Today, side saddle riding survives as a specialist discipline, preserved through competition, historical practice, and tradition-focused hunts. Modern saddles, often closest in form to the British hunting pattern, are carefully fitted and technically refined. Riding side saddle now is not about restriction, but about mastering balance, asymmetry, and precision within a highly specific system.

Viewed in full, the side saddle is neither costume nor curiosity. It is equipment shaped by social constraint, refined through craft, and altered by culture. Its story only makes sense when traced from conception through evolution and divergence to decline — and understood this way, it earns its place as serious equestrian engineering, not romantic artefact.

Escaramuza is an equestrian sport performed in side-saddle

Related Reading

In Mexico, the side saddle did not fade — it became the foundation of a living tradition.To see how side saddle riding was preserved and transformed within Mexican horse culture, read:

→ Escaramuza: Women, Horses, and Tradition in Mexico’s Arena