Lords of the Southern Plains: The Rise and Fall of the Comanche Horse Nation

Introduction

Long before the Comanche became the most feared horsemen of the American Plains, they were a Shoshone people on foot in the northern Rockies — hunters, travellers, and traders who lived by the rhythm of the mountains. Nothing in their early story suggested they would become one of the greatest mounted cultures the world has seen. That transformation began with the arrival of the horse, and from that moment on, the Comanche rewrote the map of North America.

This is the story of how a people reshaped their destiny through the saddle — and how their rise and fall mirrors the rise and fall of the horse itself on the plains.

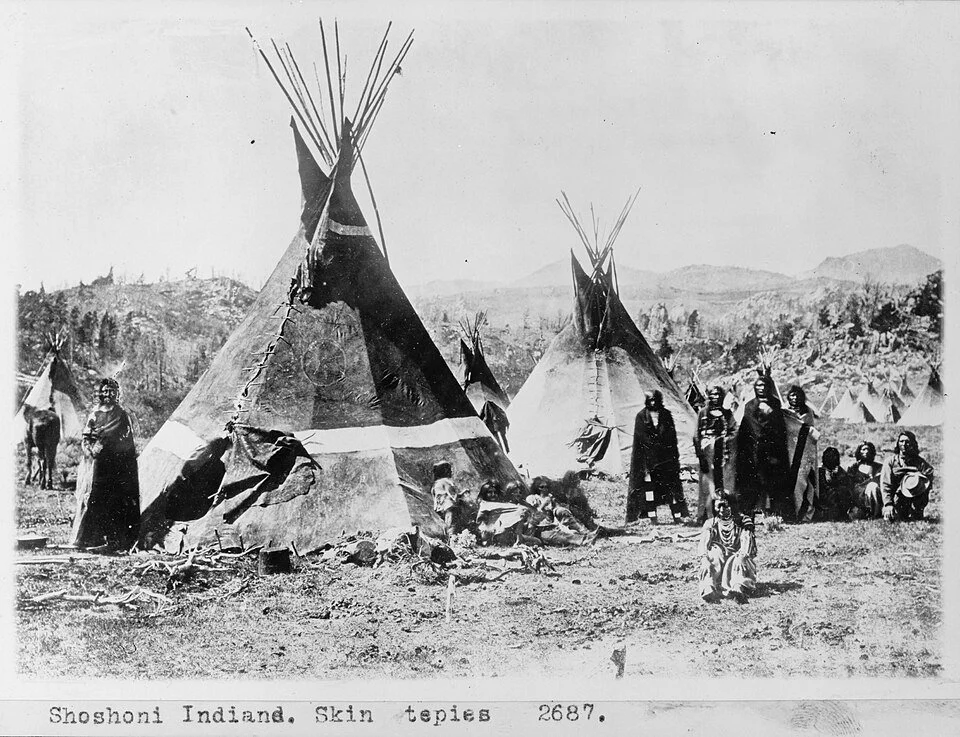

Shoshoni Indians next to their tipi

Origins: Before the Horse

In the early 1600s, the ancestors of the Comanche lived as part of the Eastern Shoshone. Life was mobile but limited by the simple reality of being on foot. Bison hunting required careful ambush, movement was slow, and power on the Plains belonged to those who could cover distance quickly.

That changed when the Spanish horse escaped into Indigenous hands.

Turning Point — When the Horse Arrived (1680–1700)

When the Pueblo Revolt erupted in 1680, thousands of horses fled Spanish control. Many ended up with Plains tribes, accelerating a transformation already underway. Among the Shoshone, a southward branch adopted the horse so rapidly and so completely that they became a new people in the eyes of those around them.

They called themselves Nʉmʉnʉʉ — The People. Others called them Comanche.

The horse unlocked the Southern Plains: a world of endless grass, deep herds of bison, and open horizons perfect for mounted life. Within a generation, the Comanche were no longer mountain people — they were lords of the prairie..

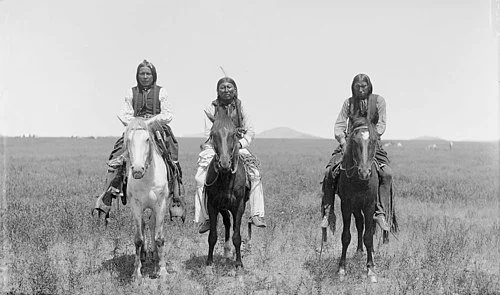

Comanche warrior and his horse

Comancheria — The Birth of a Power

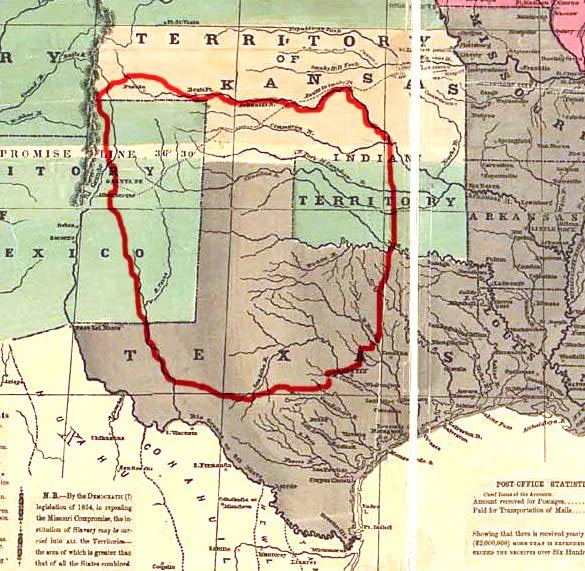

By the mid-18th century, the Comanche had pushed southward with extraordinary speed. They displaced the Apache, took control of critical waterholes, shaped alliances, and secured the richest hunting grounds on the Plains.

What emerged was Comancheria — an immense territory stretching across present-day Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, and New Mexico.

This wasn’t a "tribal homeland" in the European sense. It was a living, breathing landscape shaped by mobility, negotiated access, practical diplomacy, and overwhelming cavalry skill.

The Spanish didn’t expand into Comancheria — they negotiated their survival around it.

Map of Comanche territory

Masters of the Horse — The Comanche Ascendancy

The Comanche reached their height through a horse culture unlike anything in North America.

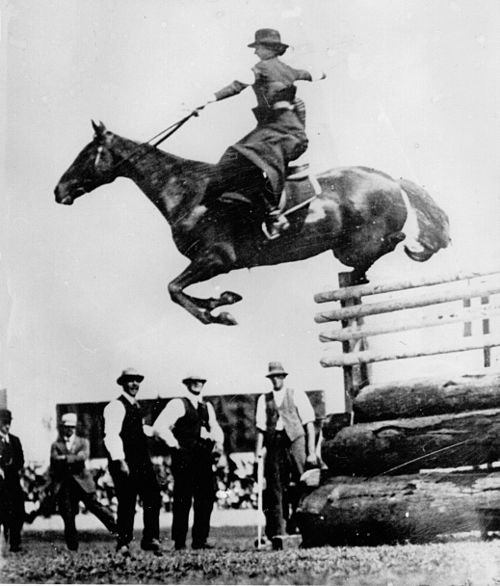

A Riding Style Built for War

Comanche horsemanship was built for movement, shock, and control. Riders often went without saddles or relied on little more than a thin pad, guiding their horses through knee pressure, balance, and subtle shifts of body weight. At speed, they could fire accurately, turn sharply, or slip low along the horse’s flank, using the animal itself as moving cover.

This was not reckless riding, but a refined partnership. Horses were trained to respond instantly, to surge, stop, or pivot on instinctive cues. European observers struggled to describe what they were seeing, often resorting to the comparison of horse and rider as a single organism — not man mounted on horse, but something closer to a centaur.

Comanche painting by George Catlin

Herds and Breeding

Although the Comanche kept no written genealogies or stud books, they practised a practical and demanding form of selective breeding. Mares formed the foundation of the herd, valued for endurance, soundness, and the quality of their offspring. Stallions were chosen for calmness under pressure, stamina, and proven performance in hunting or war.

Large herds allowed natural selection to reinforce these choices. Horses that could not keep up on long rides, endure harsh winters, or remain steady amid chaos were simply not bred. Over generations, this produced a tough, wiry Plains horse — fast, resilient, and perfectly suited to a life of constant movement.

Herd of horses on the plains

Economy and Diplomacy

Horses reshaped every layer of Comanche life. They were wealth, transport, military advantage, and diplomatic currency all at once. Through trade and raiding, the Comanche supplied horses across the Plains, embedding themselves at the centre of regional economies.

Spanish authorities, unable to defeat them militarily, were forced into negotiation. Unlike most Indigenous nations, the Comanche were treated as a sovereign power — not out of generosity, but necessity. Their control of territory, trade routes, and horse herds made them indispensable and dangerous in equal measure.

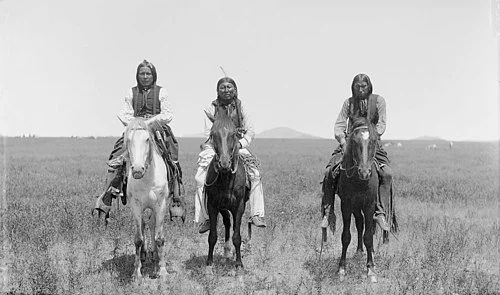

Comanche riding along in single file

Strain on the Horizon

Power rarely fades all at once. For the Comanche, the pressures that weakened their world arrived gradually, compounding over decades. Repeated outbreaks of smallpox reduced population and leadership, severing the transmission of knowledge that sustained Comanche life.

At the same time, commercial hide hunters armed with long‑range rifles devastated the buffalo herds that formed the economic and spiritual foundation of the Plains. As bison disappeared, so too did the freedom of movement that had defined Comancheria.

By the mid‑19th century, these losses coincided with intensifying settler expansion. Texas Rangers and U.S. forces brought repeating firearms, fortified settlements, and a political mandate to dismantle Indigenous control of the Southern Plains.

Still, even under mounting pressure, the Comanche remained skilled, elusive, and dangerous opponents — their horsemanship intact, but the world around them closing in.

The Breaking Point — The End of Comancheria

The decisive blow came during the Red River War.

U.S. forces targeted the Comanche’s greatest strength: their horses.

At Palo Duro Canyon, soldiers captured and killed more than a thousand horses, effectively removing the Comanche’s ability to move, fight, or feed themselves.

Once a mounted nation loses its mounts, its independence disappears with them.

In 1875, the last free Comanche bands surrendered at Fort Sill, ending almost two centuries of dominance on the Plains.

Painting of Comanche by George Catlin

Native American prisoners

Aftermath — Adaptation and Survival

Reservation life was a profound rupture for a people whose entire worldview had been shaped by motion, open space, and the horse. Forced settlement at Fort Sill in present-day Oklahoma brought an end to the Comanche as a mounted power, but it did not end Comanche identity.

In the generations that followed, horses never fully disappeared from Comanche life. While large free-ranging herds were no longer possible, horsemanship persisted in quieter, more domestic forms — in ranch work, farming, and everyday riding. Knowledge that had once been passed on the open plains was carried forward within families, adapting to new realities rather than vanishing.

Today, the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma continues to maintain cultural connections to the horse through ceremonies, community events, and educational programs. Horses appear in tribal gatherings, parades, and cultural demonstrations, not as instruments of war, but as living symbols of endurance, memory, and identity.

Comanche Nations fair