Soul of Spain – Part II:

The Vaquero

Across the wide dehesas of southern Spain, where cattle graze beneath oak trees and dust lifts in the afternoon heat, one figure has long stood as both worker and symbol: the vaquero.

More than a cattleman, the vaquero is part of Spain’s rural soul — a horseman shaped by the land, by history, and by a style of horsemanship refined through practical experience. His methods, traditions, and quiet mastery have become woven into Spain’s identity, influencing how the land was worked and how the horse became embedded in national character.

A Product of the Land

The vaquero is closely tied to the landscape that formed his role. In the dry, open regions of southern and western Spain — particularly in Andalusia, Extremadura, and Castile — vast estates known as dehesas shaped the rhythms of rural life. These were not gentle pastures, but sprawling, uneven tracts of scrub, stone, and oak groves, where cattle grazed semi-wild across unfenced ground. Managing these herds required a mounted horseman capable of reading the terrain, understanding animal behaviour, and riding with precision.

The environment left few alternatives. Long distances, harsh heat, and constant movement made horseback work essential. The horse enabled faster travel, closer control of livestock, and a working range far beyond what could be covered on foot.

Over time, the vaquero developed a practical knowledge of the land and livestock. His riding was shaped not by style, but by necessity — a functional response to the conditions around him.

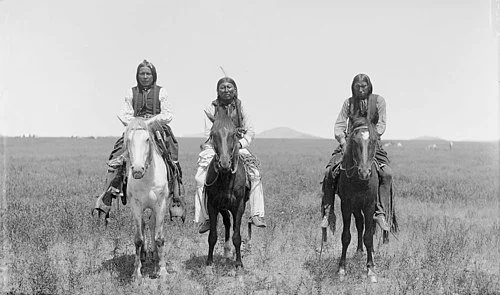

Vaquero horseman working cattle

A Style Shaped by History

What we now know as doma vaquera — the riding style of the vaquero — evolved over centuries, shaped by the layered history of the Iberian Peninsula. Moorish horsemen, who ruled much of Spain for over 700 years, brought techniques centred on rein finesse, light contact, and balance. These principles became the foundation of Spanish horsemanship. Later, Spanish light cavalry refined the style further, introducing more formalised methods and the elegant use of the curb bit (bocado).

The result was a distinct rural tradition. The vaquero rode one-handed, leaving the other free for managing cattle with a pole or rope. Horses were introduced gradually to tack, beginning with a cavesson or hackamore and only later graduating to the bocado — not as a tool of control, but as a mark of maturity and softness.

Doma vaquera is not a stylised performance; it is a working language. Each cue is minimal, each movement purposeful. It remains a style born of necessity — precise, fluid, and always grounded in the demands of the land.

Doma Vaquero riding style showcased in horse show

The Vaquero and the Andalusian Horse

At the centre of the vaquero’s work was the Andalusian horse. Compact, strong, and agile, this native Iberian breed was chosen for its suitability to the job. Its conformation and temperament made it ideal for long days in the saddle, for tight manoeuvres around livestock, and for the kind of fine-tuned communication required in open terrain.

As work demands shaped training approaches, they also influenced the breed itself. The Andalusian became known for being quick-thinking but not reactive, sensitive yet stable, bold in rough country, and calm among herds.

While other regions bred for speed or spectacle, the Andalusian was refined for feel, responsiveness, and versatility. In return, it provided the vaquero with a capable partner that matched the landscape and demands of rural Spain.

Even today, the Andalusian remains recognised internationally — not only for its movement, but for its trainability and temperament. That legacy was forged in practical work, not ceremony.

Andalusian horse dressed in traditional Vaquero style

A Living Symbol of Spanish Identity

Over generations, the vaquero became a cultural emblem — not through image-making, but through his long-standing presence in the fabric of Spanish rural life.

His clothing and tools became regionally distinctive. The flat-brimmed sombrero cordobés, the long suede zahones, and the engraved bocado all reflected local identity as much as professional function.

Today, the vaquero's traditions remain active. His methods are still used in ranching regions and are demonstrated at local festivals, not as re-enactment but as continuity. Knowledge continues to pass through generations — through time in the saddle rather than formal instruction.

In a changing Spain, the figure of the vaquero continues to represent a way of life rooted in horses, land, and practical experience.

Vaquero horseman at local festival

A Lasting Legacy

The Vaquero’s legacy did not stop at Spain’s borders. As Spanish riders and settlers moved into the Americas, vaquero methods became the foundation for other horse cultures — from Mexican charros to American cowboys and South American gauchos. His use of specific bits, saddles, and cattle-handling techniques was adapted, region by region, into new environments and needs. The groundwork for many global stock-riding traditions traces back to this figure shaped by Spain’s rural terrain.

In working estates and riding schools, in fairs and quiet country lanes, traces of vaquero tradition still endure. Not as nostalgia, but as a method that remains effective, time-tested, and culturally significant.

For Spain, the vaquero is more than a historical figure. He represents a living link between geography, history, and horse culture — a figure whose influence is still visible in the way horses are ridden, trained, and understood across the world today.